On December 28, an editorial in the New York Times broached an eight-part series on abortion rights that is positively astonishing. It is clearly the most rabid defense of abortion ever published by the mainstream media. The first installment was published on December 30; it will end on January 20. The entire series is now available online.

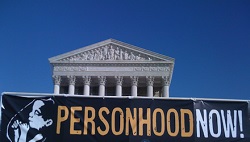

Why is the Times running this series? The best explanation is found in the first paragraph of the 8th installment. "Now that the Supreme Court has a conservative majority that appears inclined to overhaul Roe v. Wade, it is likely only a matter of time before women's reproductive rights are ratcheted back." Its central fear is a ruling declaring the unborn child worthy of "personhood" rights.

The thesis of the series is that any attempt to recognize the humanity of the unborn baby threatens women's rights. According to the Times, laws that restrict abortion rights are ultimately about controlling women's sexuality, and no group is more preyed upon than brown and black women. Peppered with anecdotes, the series pays almost no attention to data: highly debatable assertions are routinely made without any supporting evidence.

Many defenders of abortion rights will at least acknowledge the competing right to life of children in utero. But not the authors of this series. Nascent human life is referred to as nothing more than "clusters of cells," as if these human biological properties were mere stuff.

It is this mental block—the refusal to admit the obvious—that allows the Times to object to prosecuting a woman for murder after her attempted suicide resulted in killing her eight-month-old baby. Similarly, it cannot understand why a jury convicted a pregnant woman driver of killing three persons after she drove her car over a double-yellow lined road on Long Island, crashing into another car: the driver of the other car, his wife, and the woman's eight-month-old baby were killed (the reckless driver was under the influence of drugs and alcohol). The jury said she needlessly caused the death of her daughter (who died five days after the accident) because she was not wearing a seatbelt.

Those two babies would have lived had their mothers not acted irresponsibly, but that gets lost in the fog of abortion rights run amuck.

The contortions that the Times goes through trying to deny reality is remarkable. For example, it offers the account of a "visibly pregnant woman" seeking an abortion in another state having to deal with airport security officers. They wished her "a happy Mother's Day." One of them "cheerily" asked, "Is this your first?" The Times branded her experience "a surreal journey." What is truly surreal is the paper's interpretation.

What is really gnawing at the Times is the recent emergence of laws protecting the personhood of unborn babies. It calls them "an extreme legal argument with little precedence in American law before the 1970s." However, the common law in Western civilization typically held that a pregnant woman convicted of a capital offense could not be executed, thus paying homage to the existence of an innocent human being. No matter, the newspaper is right to say that personhood legislation is of recent vintage.

There is a reason for this, and it has nothing to do with what the Times says: it attributes this to a move by Republicans in the 1970s to criminalize abortion. In point of fact it was technology, not politics, that proved to be the key to protecting the personhood status of unborn children. To be exact, ultrasound made the difference. Invented in the 1950s, it was not used with any regularity in U.S. hospitals until the 1970s.

How did ultrasound change the debate? Consider what Dr. Bernard Nathanson, one of the nation's leading abortion-rights advocates in the 1960s and 1970s, said about the subject. [Note: This Jewish atheist later became a pro-life champion and converted to Catholicism.]

"By 1984, however, I had begun to ask myself more questions about abortion: what actually goes on in an abortion? I had done many, but abortion is a blind procedure. The doctor does not see what he is doing. He puts an instrument into a uterus and he turns on a motor, and the suction machine goes on and something is vacuumed out; it ends up as a little pile of meat in a gauze bag. I wanted to know what happened, so in 1984 I said to a friend of mine, who was doing 15 or maybe 20 abortions a day, 'Look, do me a favor, Jay. Next Saturday, when you are doing all these abortions, put an ultrasound device on the mother and tape it for me.'

"He did, and when he looked at the tapes with me in an editing studio, he was so affected that he never did another abortion. I, though I had not done an abortion in five years, was shaken to the very roots of my soul by what I saw."

The precision of sonograms (the actual picture of an ultrasound) is much more advanced today. It would be instructive to learn what the editors of the New York Times might think of such images. Would they see "clusters of cells," or small human beings?

The most controversial part of the series is found in the 4th and 5th installments, especially the 4th. It would be hard to find a more unpersuasive, and disturbing, attempt to discredit the damage done to unborn babies by their drug-ridden mothers. Moreover, this section of the series, while condemning racism, actually promotes it.

Part 4 condemns what it says is the "myth of the 'crack baby.'" It criticizes the mainstream media (it includes the Times) for over- dramatizing the physical and psychological damage done to babies by their cocaine-using mothers. Reading this part of the series makes one wonder just how far radical pro-abortion reporters will go in their defense of the indefensible.

The idea of "crack babies," the newspaper says, is a combination of "bad science and racist stereotypes." These twin evils, we are told, were "debunked by the turn of the 2000s." Really?

Somehow I must have missed this story. So I looked forward to reading why the "bad science" was wrong. But there was nothing there.

"The Legacy of the Myth" is the title of a section of Part 4 that led the reader to believe that the evidence would be forthcoming. It begins by saying, "Researchers debunked the 'damage generation' theory numerous times, finding no indication that children exposed to crack in the womb faced long-term debilitation and that the effects once tied to exposure were attributable to other drugs like alcohol and tobacco, or to factors associated with poverty, including homelessness and domestic violence."

Let's break down that sentence. Which researchers? Who are they? Why didn't the article tell us? And even if other drugs can cause similar problems—which is nowhere proven—why is this proof that the "damage generation" theory of crack-using pregnant mothers has been debunked?

The underscored words are a link to a book, one which supposedly offers the evidence the Times says exists. I accessed a copy of it and nowhere does it offer any such evidence. The book, Somebody's Children: The Politics of Transracial and Transactional Adoption, by Laura Briggs, is more sociological than physiological. This makes sense: The author is not a professor of the natural sciences—she is a professor of Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies.

The relevant chapter in this book, "'Crack Babies,' Race and Adoption Reform, 1975-2000," does not attempt to debunk the "bad science." Just as important, the fact that it covers "race and adoption reform" in the last century does nothing to show why babies born today of crack-using mothers are not seriously impaired.

No wonder the Times likes this book. The author trashes people like Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Newt Gingrich, Bill Bennett, and Charles Krauthammer—all of whom have expressed concerns about low-income black families (almost all headed by a single woman) and the evils of drug addiction. Such politics may make for a good read in the academy, but it does nothing to shine light on why any of them were wrong.

In 2016, the National Institute on Drug Abuse concluded that besides the damage done to the women who use crack, "Babies born to mothers who use cocaine during pregnancy are often prematurely delivered, have low birth weights and smaller head circumferences, and are shorter in length than babies born to mothers who do not use cocaine."

It added that "scientists are now finding that exposure to cocaine during fetal development may lead to subtle, yet significant, later deficits in children. They include behavior problems (e.g., difficulties with self-regulation) and deficits in some aspects of cognitive performance, information processing, and sustained attention to tasks—abilities that are important for the realization of the child's full potential."

Other studies describe learning disabilities that result from a damaged central nervous system and congenital heart diseases. Such children tend to do poorly in school, have social problems, and a host of other developmental disabilities.

Forget about the science for a moment. What responsible professor in a medical school would instruct students that crack-addicted mothers have little to worry about? What responsible professor in a medical school would engage students in a social analysis of racism, instead of warning about the damage being done to the physical and psychological well being of babies conceived by cocaine-using mothers?

The Times is right to note that racism has affected this issue, but it is looking in the wrong direction: It should look in the mirror. We would expect white supremacists to downplay the effects of crack on unborn black babies, not the alleged opponents of racism. The newspaper is so totally obsessed with abortion rights—it has reached a state of delirium—that it is willing to slight the harm being done to black children by their cocaine-addicted moms, all because of the necessity of denying them personhood.

It may take some time before the idea of granting personhood status to unborn babies catches on nationwide, but the vector of change is moving that way. This is why the New York Times sees this as such a frightening prospect.

Sign Up to Receive Press Releases:

Sign Up to Receive Press Releases: